Montreux Collaborative Blog

Precipitated aid transition in health – priority actions for low-and-middle income-countries

Hélène Barroy, Susan Sparkes, Kalipso Chalkidou (WHO/HQ)

With contributions from Christabel Abewe (WHO/Uganda), Kingsley Addai Frimpong (WHO/Ethiopia), Georgina Bonet (WHO/AFRO), Riku Elovainio (WHO/Democratic Republic of Congo), Sophie Faye (WHO/AFRO), Jayendra Sharma (WHO/SEARO), Tsolmongerel Tsilaajav (WHO/Vietnam), Anna Vassall (WHO/HQ), Ding Wang (WHO/Cambodia), MyMai Yungrattanachai (WHO/HQ).

Background

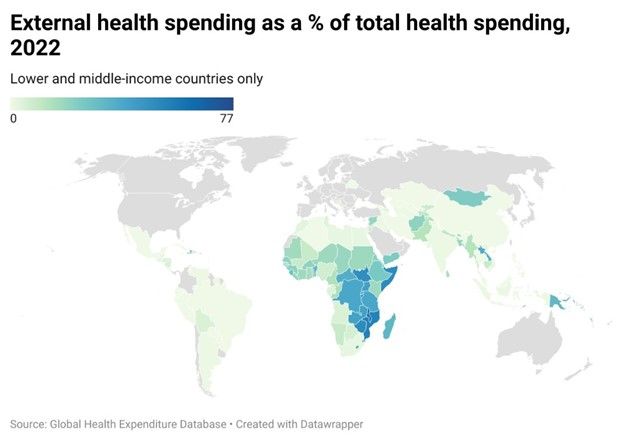

In low-and many middle-income countries, donor funding is a critical component of health financing. Since 2006, per capita external aid in low-income countries specifically (US$12.8 in 2022) has consistently surpassed domestic public spending on health (US$8.8 in 2022). This heavy reliance highlights the vulnerability of health systems to potential fluctuations in donor funding. For example, the recent and sudden freeze of US government aid, the second largest health donor globally, is having profound financial and service delivery implications, including for most vulnerable populations, for many countries (including Kenya).

In low-and many middle-income countries, donor funding is a critical component of health financing. Since 2006, per capita external aid in low-income countries specifically (US$12.8 in 2022) has consistently surpassed domestic public spending on health (US$8.8 in 2022). This heavy reliance highlights the vulnerability of health systems to potential fluctuations in donor funding. For example, the recent and sudden freeze of US government aid, the second largest health donor globally, is having profound financial and service delivery implications, including for most vulnerable populations, for many countries (including Kenya).

While acknowledging the significant disruptions caused by freezing aid flows, this challenging situation also presents a potential opportunity, and actual necessity in many cases, for renewed dialogue between donors and domestic authorities, and health and finance authorities. Despite the difficult fiscal context, this period may force a change, whereby some countries increase domestic financing for health and accelerate the efficiency with which all funds are spent. One-to-one replacement of domestic, public funds for external funds for health is neither realistic nor necessary (see Malawi); still, in many cases, a higher investment of domestic, public resources is needed to accelerate progress toward universal health coverage.

More broadly, reform to the aid architecture for health has been an issue long before January 2025. This particular moment, with US Government funding in flux, provides a window to refocus all existing donor funding for health on core government priorities and to put in place protections to mitigate against the impact of aid volatility. This aligns with the shifts put forward by the Lusaka Agenda, which stresses reforms needed to Global Health Initiatives, and the overall global health financing architecture, so that funding flows can better support domestic systems, priorities, and needs.

Over the past decade, WHO’s Health Financing team at country, regional and global levels has worked, closely with countries in building the evidence base, sharing best practices, and providing guidance to promote sustainable and efficient domestic financing for health, including through leveraging work on cross-programmatic efficiency and public financial management (PFM). In this blog, we outline practical actions that health leadership can take to mitigate the sustainability risks of the current situation and establish longer-term foundations for a smooth transition towards increasingly domestically financed health systems. We focus on a set of interconnected actions related to external resources, domestic revenues, and programme operations and organization. These three streams will need to come together in support of sustainable coverage regardless of the revenue source and require coordinated actions between donors and country leadership.

External resources

The rapid shifts in US Government funds demonstrate the potentially tenuous sustainability of external funds and call for clear and immediate actions for country leaders, in partnership with donors, to take stock and consider changes to the way aid for health flows. These actions cannot be solely driven by how much external funding for health there is in a country, but ought to be informed by how, through what systems and disbursement modalities, and for what purposes those funds flow. The freeze in US aid has revealed major issues with the lack of visibility of external flows to national authorities, making it challenging for domestic funding to step in, even when resources may be available. Actions are needed across external funding sources, with other donor reducing health aid, including France, Germany, Netherlands and the United Kingdom. These can help to plan for and take action to enhance sustainability prospects, including complementary interactions with domestic funding for health.

The rapid shifts in US Government funds demonstrate the potentially tenuous sustainability of external funds and call for clear and immediate actions for country leaders, in partnership with donors, to take stock and consider changes to the way aid for health flows. These actions cannot be solely driven by how much external funding for health there is in a country, but ought to be informed by how, through what systems and disbursement modalities, and for what purposes those funds flow. The freeze in US aid has revealed major issues with the lack of visibility of external flows to national authorities, making it challenging for domestic funding to step in, even when resources may be available. Actions are needed across external funding sources, with other donor reducing health aid, including France, Germany, Netherlands and the United Kingdom. These can help to plan for and take action to enhance sustainability prospects, including complementary interactions with domestic funding for health.

-

Establish baseline by identifying, mapping, and quantifying the in-country stakeholders, services, and programmes that aid supports to provide greater visibility of the external funding flows. This includes the modality of aid (e.g. through government PFM systems or non-governmental entities), as well as differentiating cash from in-kind support (e.g. medicines, vaccines, technical assistance). This mapping should consider funding source, funding direction, programmatic area, as well as cost category (e.g. salaries, goods and services, capital).

-

Assess alignment of current and planned donor funding to domestic priorities and systems, including by using the Lusaka Agenda financing and PFM alignment indicators, to identify potential efficiency gains through re-programming/re-channeling of existing/planned commitments.

-

Identify at-risk expenditures including those where funding has frozen, have a short time-horizon, or could become ineligible based on future donor priorities, to mitigate risks for large unplanned liabilities to domestic budgets (e.g. as is the case in the Philippines).

-

Consider transferability and complementarity of existing donor commitments within overall donor budget funding availability. This includes convening a process with all donors to consider sequencing options and whether other donor funds can help cover funding as an interim measure to complement domestic resources.

-

Negotiate for adjustment in current aid modalities to allow greater flexibility in resource allocation and use, including through pooling mechanisms, to better meet needs and priorities. Conditioned, domestic co-financing requirements (i.e. domestic financing conditioned by global health funding agencies) can also be revisited in terms of both quantity and focus in light of overall fiscal scenarios and the health budget envelope.

Domestic revenues:

Domestic, public spending should be the predominant source of funding to ensure equitable and sustainable access to health services. The reduction in donor funding must not result in increased out-of-pocket expenditures, as this would undermine financial protection and exacerbate household impoverishment. The current situation presents a strategic opportunity to reassess overall and health budget allocations, focusing on their levels, priorities, and channeling processes to explore ways to expand and refine the spending baseline. In the immediate term, critical actions for health authorities can include:

-

Conduct a rapid assessment of the macro-fiscal and health financing landscape by analyzing recent trends in government revenues, overall public expenditure, and health spending in relation to GDP and on a per capita basis. As a complement, undertake a spending review to identify potential efficiency gains, including from fund allocation procedures, channeling modalities and spending rules (e.g. gains through improved budget execution).

-

Engage in strategic discussions with finance authorities and parliamentarians to showcase the financial repercussions of actual and anticipated reductions in aid overall, and specifically for health, and its broader implications for labor, productivity, and the overall economy. Establish scenarios for budget re-prioritization, including within health envelope, in collaboration with budget authorities and mobilize senior leadership and support coalitions, including with civil society, to mitigate immediate funding shortfalls and plan for broader strategic re-allocations within PFM regulatory frameworks (see Kenya’s experience).

-

Evaluate additional sources of revenue, and based on debt status, explore with finance authorities potential avenues for additional borrowing to augment fiscal capacity (e.g. in Nigeria with a new World Bank loan), including through leveraging newly established funding mechanisms for health-related purposes such as the International Monetary Fund Resilience and Sustainability Facility, as well as potential debt relief options.

-

Streamline PFM procedures within existing regulatory frameworks, making domestic resources better allocated and executed in health, including through contracted NGOs, and ensure consolidated financial monitoring and reporting through established financial information systems, potentially connected with health information systems to enable accountability for results.

-

Avoid the new creation of, and integrate existing, extra-budgetary, parallel, separate entities and processes (e.g. donor-related project implementation units or issue-specific contingency funds) to channel and account for both domestic and external resources through government structures and spending units.

-

Work toward reducing financial fragmentation through a planned consolidation process of existing financing schemes and harmonization of health purchasing functions.

Programme composition and organization

Previous experience, for example graduation from Gavi, Global Fund or the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) funding, shows that donor transition is not purely financial. Rather actions often need to be taken to restructure, reshape and reorganize externally supported programmes and services to align to domestic priorities and systems. This can improve efficiency and enhance coverage sustainability by better incorporating externally financed activities into the routine activities of the health system, in the case they have not been previously. After establishing the external resources baseline referenced above, actions to deliberately transition and modify externally financed programmes and services, whether implemented vertically or not, include:

Previous experience, for example graduation from Gavi, Global Fund or the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA) funding, shows that donor transition is not purely financial. Rather actions often need to be taken to restructure, reshape and reorganize externally supported programmes and services to align to domestic priorities and systems. This can improve efficiency and enhance coverage sustainability by better incorporating externally financed activities into the routine activities of the health system, in the case they have not been previously. After establishing the external resources baseline referenced above, actions to deliberately transition and modify externally financed programmes and services, whether implemented vertically or not, include:

- Identify functional areas for integration within programmes and across the health system through a clear transition plan that focuses on efficiency enhancements and targets areas where duplication likely already exists (e.g. supply chains, information systems, supervision, surveillance). This process should ensure continuity in services, including for vulnerable population groups.

- Develop an integration framework and roadmap to carefully guide the service integration process ensuring smooth delivery of integrated health services, with primary care at the core. This includes ensuring that PFM procedures support effective and efficient use of resources at the front lines that should be able to access and use resources in a flexible and accountably way.

- Assess the cost-effectiveness of donor-supported programmes and interventions as a means to re- or de-prioritize certain activities, including those that should be introduced or scaled up, as well as those that are not aligned with domestic priorities, fit within fiscal realities, or are an inefficient use of resources. This system re-orientation process involves shifts in both funding modalities, as well as in service delivery mechanisms, in particular to strengthen integrated, primary care services.

- Focus on transitioning human resources-related costs to domestic funding to ensure service continuity, including by focusing on salary alignment, cadre integration, and provider payment and contracting modalities. Consider implications of major capabilities gaps at service level caused by aid freezes or reductions (e.g. contracted personnel) and re-focus existing funding on strengthening domestic institutional and technical capacities.

- Review existing procurement modalities across donor-funded activities as a starting point to streamline, integrate and capacitate for domestic procurement, supply distribution, and support efforts to develop domestic production of key products and medicines.

What’s next?

Sudden changes in the health financing landscape, whether from external or domestic shocks necessitate that country leaders manage, often having to pivot activities, to make the best use of their domestic systems and resources. We are seeing rapid action by many countries to address the current shock to external health aid, as well as to plan for potential future deceases. For example, in Uganda a recently adopted mitigation plan lays out a path to integrate certain donor funded activities within the domestically financed health system and services. While not easy, the actions laid out in this blog provide a framework that can guide deeper analysis and understanding in countries to inform future realignment processes and system reorganization.

Sudden changes in the health financing landscape, whether from external or domestic shocks necessitate that country leaders manage, often having to pivot activities, to make the best use of their domestic systems and resources. We are seeing rapid action by many countries to address the current shock to external health aid, as well as to plan for potential future deceases. For example, in Uganda a recently adopted mitigation plan lays out a path to integrate certain donor funded activities within the domestically financed health system and services. While not easy, the actions laid out in this blog provide a framework that can guide deeper analysis and understanding in countries to inform future realignment processes and system reorganization.

25 February 2025